The Mardellen

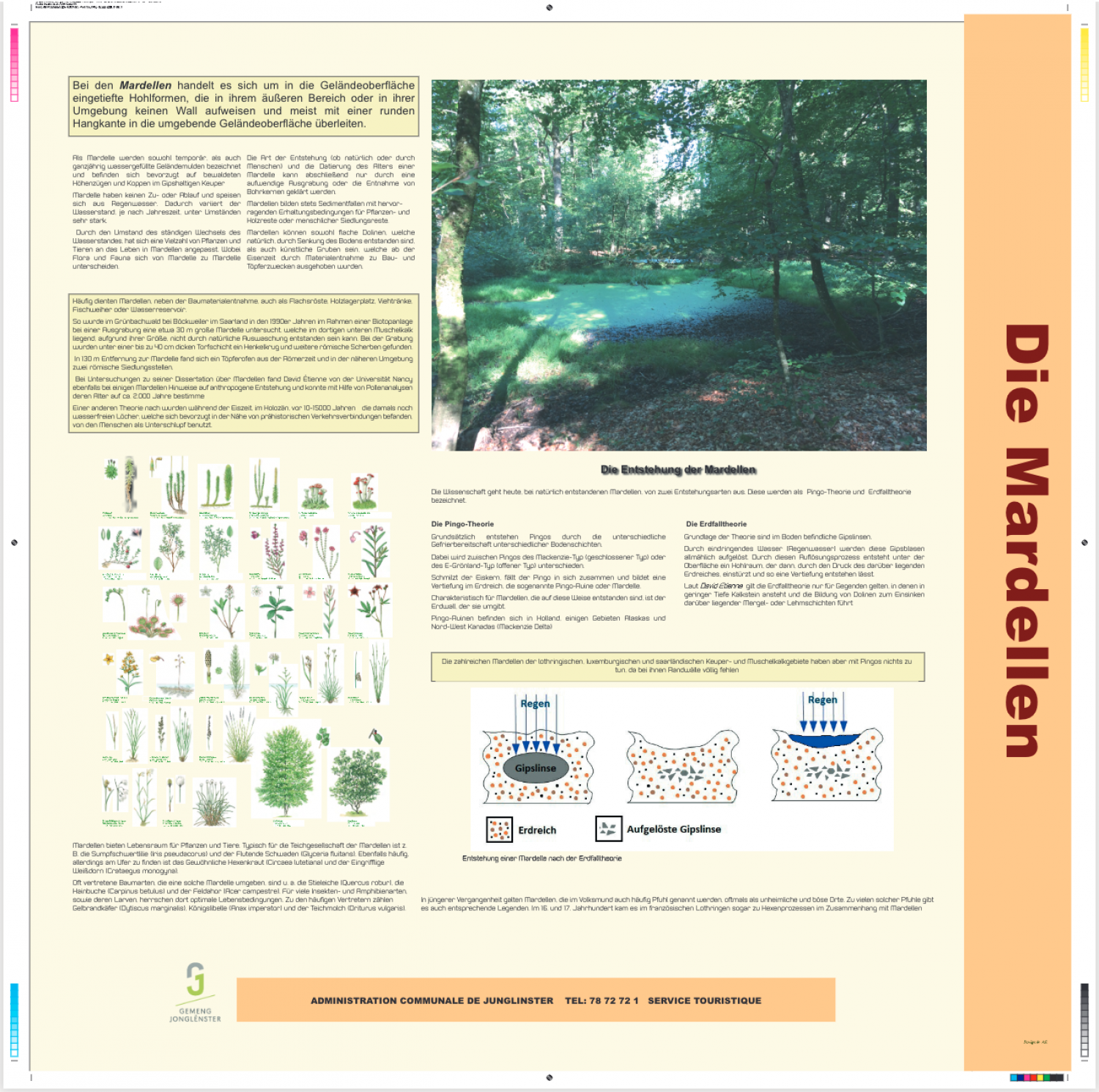

Mardellen are depressions in the surface of the landscape in which have no wall in their external or surrounding areas and typically transition into the surrounding surface via a rounded sloping edge. A mardelle refers both to temporary and year-round, water-filled depressions which primarily occur on wooded heights in the gypsum-containing Keuper. Mardellen have no in- or outlet and are filled by rainwater. The water level, therefore, varies widely depending on the season. Due to the constantly changing water level, a variety of plants and animals have adapted to life in mardellen, though flora and fauna differ from one mardelle to another. The origin of a mardelle (whether natural or human) and the dating of its age can only be discovered through extensive excavation or the removal of core samples. Mardellen always provide sediment traps with exceptional preservative properties for plant and wood remains, or the remains of human settlements. Mardellen can arise from flat sinkholes, which occur due to the sinking of the ground, or as artificial trenches which were excavated from the Iron Age onward to remove materials for building and pottery-making purposes. Alongside obtaining building materials, mardellen also often served as retting ponds, wood storage sites, livestock waterholes, fish ponds or water reservoirs. In Grünbach forest near Böckweiler in the Saarland, a 30 m-wide mardelle was investigated in the 1990s as part of excavations in a biotope preservation area. Due to its size, given the shell limestone underneath, it could not have occurred naturally. During the excavation, under a layer of peat up to 40 cm thick, a pitcher and other Roman fragments were found. 130 m away from the mardelle, a kiln from the Roman era was found, along with two Roman settlement sites in the surrounding area. In his doctoral research on mardellen, David Étienne from the University of Nancy also found evidence of human origin in some Mardellen and was able to use pollen analysis to determine their age to be approx. 2000 years. According to another theory, the holes – still free of water and located primarily near prehistoric transit routes – were used by humans as shelter during the Ice Age, in the Holocene Era 10-15,000 years ago. [plants] Peat Moss* Sphagnum 2-30 am | July – September (spores ripen) Common haircap moss Polytrichum commune 10-40 cm | June – August (spores ripen) Marsh club moss Lycopodium inundatum 2-10 cm | June – October (spores ripen) Stiff club moss Lycopodium annotinum 10-30 cm | August – September (spores ripen) Pixie-cup lichen Cladonia pyxidata 1-2 cm Madame’s pixie-cup lichen Cladonia coccifera 2-4 cm Bog cranberry Vaccinium oxycoccos 2-6 cm | May – August Bog bilberry Vaccinium uliginosum 30-100 cm | May – July European blueberry Vaccinium myrtillus 15-30 cm | April – June Common heather Calluna vulgaris 30-100 cm | August – October Cross-leaved heather Erica tetralix 15-50 cm | June – September Bog rosemary Andromeda polifolia 15-30 cm | May – August Round-leaved sundew Drosera rotundifolia 5-20 cm | July – August Bogbean Menyanthes trifoliata 15-30 | May – July Chickweed wintergreen Trientalis europaea 5-20 cm | May – July Marsh willowherb Epilobium palustre 10-50 cm | July – September Purple marshlocks Potentilla palustris 30-100 cm | June – July yellow loosestrife lysimachia vulgaris 50-150 cm | June – August Lesser bladderwort Utricularia minor 5-15 cm | June – August Marsh horsetail Equisetum palustre 10-60 cm | June – September Least bur-reed Sparganium natans 10-50 cm | May – August Goose corn Juncus squarrosus 10-35 cm | June – August Soft rush Juncus effusus 30-120 cm | June – August Woollyfruit sedge Carex lasiocarpa 30-100 cm | May – June Fibrous tussock-sedge Carex appropinquata 70-110 cm | May – June Purple moor-grass Molinia caerulea 30-200 cm | July – September Common cottonsedge Eriophorum angustifolium 20-90 cm | March – May Sheathed cottonsedge Eriophorum vaginatum 50-70 cm | March – May European white birch Betula pubescens 5-20 m | April - May Alder buckthorn Frangula alnus 1-4 m | May – June Mardellen offer a habitat or plants and animals. Typical members of the pond ecosystem of the mardelle include the yellow flag iris (Iris pseudacorus) and floating sweet grass (Glyceria fluitans). Equally commonly, broad-leaved enchanter's nightshade (Circaea lutetiana) and single-seeded hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) are found on the banks. Common species of trees that surround such mardellen include the European Oak (Quercus robur), the European hornbeam (Carpinus betulus) and the field maple (Acer campestre). Or many species of insect and amphibian, as well as their larvae, these spaces offer optimal conditions. Some of the most common examples include the great diving beetle (Dytiscus marginalis), the emperor dragonfly (Anax imperator) and the smooth newt (Triturus vulgaris). How Mardellen form With regard to naturally occurring mardellen, scientists distinguish between two means of formation. These are called the Pingo Theory and Earth-Fall Theory. The Pingo Theory Pingos occur due to the relative tendency of various layers in the ground to freeze. A distinction is made between the Mackenzie (close) type and the E-Greenland (open) type. If the ice core melts, the pingo collapses and creates a depression in the ground, the so-called pingo ruin or mardelle. Characteristic of mardellen formed in this way is the wall of earth surrounding them. Pingo ruins are found in Holland, certain parts of Alaska and north-west Canada (Mackenzie Delta). The Earth-Fall Theory The basis of this theory is the lentil-shaped gypsum deposit in the ground. Due to the infiltration of water (rainwater), these gypsum bubbles are slowly dissolved. As a result of this dissolution process, a hollow space forms under the surface, which then collapses under the pressure of the earth above it, creating a depression. According to David Étienne, the earth-fall theory only applies in areas where there is limestone at a shallow depth and the development of sinkholes causes the collapse of the marl and clay layers above. The numerous mardellen in the Keuper and shell limestone regions of Lorraine, Luxembourg and Saarland, however, have nothing to do with pingos because they have no walls around their rims. [Diagram:] Gypsum deposit Earth Dissolved gypsum Creation of a mardelle according to the earth-fall theory

Download Flyer (PDF)